In November of 2015, shortly after beginning my career as a doctoral student at the Graduate Center, I received an email from Victor Papa, president of the Two Bridges Neighborhood Council. Papa expressed his interest in commemorating the Italian American community of the former Lung Block, an area on the Lower East Side subject to proto-gentrification during and beyond the Progressive Era. I had written about the topic for my master’s thesis, and had met Papa a year prior, while conducting research in loco. We had, however, fallen out of touch until he stumbled upon my work on Academia.edu as a result of an haphazard Google query on the allegedly nefarious living conditions of the block.

As New Yorkers, we often underline with enthusiasm the city’s unique proclivity to a kind of serendipity for opportunities. Especially for academics, New York City and its cultural scene may feel like a perennial conference – with connections waiting to be made, plenty of opportunities to showcase our own scholarship and be exposed to influential work.

One could argue that the Internet provides a similarly serendipitous space. Not only has the web changed the ways in which we, as researchers and as teachers, interact with each other and with the general public, but it also reshaped the concept of academic presence altogether. Through social media, academic social networking sites (ASNS), and blogging and micro-blogging platforms, that space has now become less ephemeral and more democratic – think, for example, of the considerably lower (financial, physical, and cultural) barriers to access its resources, compared to an academic conference.

The traces we leave in each of those sites create our digital academic identity. In early September, I led my first workshop as a Digital Fellow, an introduction to Digital Academic Identity and WordPress. After a brief survey of outlets available for academics to disseminate their work on the web, my co-hosting fellow Kristen Hackett and I focused primarily on creating a landing page on our very own CUNY Academic Commons. While this blog post is by no means a substitute for the workshop (offered regularly by the Digital Fellows; I strongly encourage the reader interested in the topic to attend its next iteration), I want to emphasize some points of discussion and a few best practices that emerged from it.

What is a digital identity? Why should I care?

Last Spring, Future Initiatives Fellow Christina Katopodis wrote about finding herself on the web before going on the job market. Her reflections offered a valuable point of departure for my workshop:

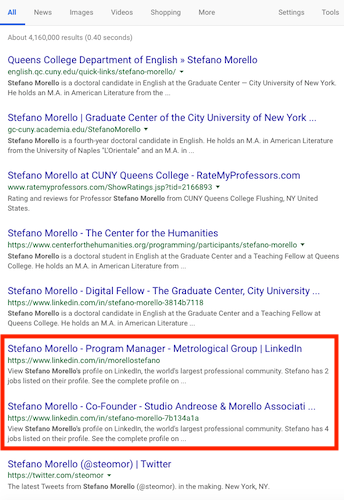

Try to google yourself.

What did you find?

Did your search results lead to the wrong people? Perhaps to the Facebook or Linkedin profiles of a digital doppelganger?

Did your search results lead to the wrong resources? A Rate My Professor page with ratings from your freshman year as a teacher? A blog post on Catcher in the Rye you wrote for an undergraduate course? An outdated department page over which you have no control?

As the exercise showed us, if we don’t pro-actively build our own digital identity, search engines will do it for us. There is hardly any way to escape it, especially in countries, such as the United States, where there is no legislative requirement to safeguard the so-called “right to be forgotten.” Despite the many safety measures we can take to limit our imprints on the web, we cannot be completely stealthy, nor delete all the traces we leave behind. We can, however, push some of that information to the background by creating (and pushing forward) new content that represent our work as a researchers, scholars, and teachers.

Ok, I’m on board. I don’t want search committees to find the Live Journal from 2004 where I wrote all about my crush on Pete Wentz. What now?”

What follows is a brief overview of web platforms available for academics to improve their visibility and that of their work.

For scholars who have some publications under their belts, Google Scholar is a good place to begin. Google Scholar is a freely accessible web search engine that indexes the full text or metadata of scholarly literature across an array of publishing formats and disciplines. In other words, with a few clicks, Google Scholar allows you to create a profile and link it to the publication indexed in its database.

When we hear Academic Social Networking Sites (ASNS), most of our minds’ immediately go to Academia.edu and Research Gate. These sites allow users to upload academic articles, abstracts, and links to published articles; track demand for their published articles; and engage in professional interaction, discussions, and exchanges of questions and answers with other users. As many of you may know, Academia.edu has often sparked controversy in the academic community – especially due to its for-profit nature and its attempt to capitalize on our work. I echo Kathleen Fitzpatrick and encourage you to consider non-proprietary alternatives such as Humanities Commons, CUNY Academic Commons, HASTAC, and CUNY Academic Works.

Blogging platforms and social media can also serve as precious platforms to encourage collaborative work (for example, it is not uncommon to use tweets and blog posts to solicit advice and feedback on our work) and to open up and promote your scholarship to both an academic and a non-academic audience. Just remember that more visibility also results in more exposition – beware of online harassment and be prepared to handle it. We can also use these tools as part of our pedagogy, to create community and momentum that extends beyond the classroom.

Remember: the kind of knowledge you produce and circulate on the web is also part of your repertoire and a valuable contribution to the conversations you are entering as a scholar.

Finally, the end goal of our workshop was to enable attendees to create their own academic website on the Commons. Think of your landing page as your best bet to sway attention from your Facebook account; a central hub for your academic identity; a comprehensive portfolio of your work; a virtual space where you can be in control of aesthetic, content, and structural choices. Your personal website could include resources such as:

- Your CV (either in an interactive form, as a PDF, or both);

- Portfolios of your publications, digital projects, and course websites/syllabi;

- Your teaching statement and/or your faculty diversity statement;

- Links to your social media;

- A contact page;

- A blog and/or podcast.

You can find some good examples of personal academic websites here, here, and here, all created by GC students. If you have some ideas you’d like to implement on your personal website and are unsure as to how you can bring them to life, the Digital Fellows are available during office hours to guide you through the process!

“Any other advice?”

Well, yes.

Aim for Coherence. While each web outlet potentially taps into a different audience, you should aim for consistency and for creating a “globally recognized avatar.” This is achieved, for example, by using the same headshot and bio on different websites, reiterating your voice and your priorities as a scholar, or linking your profiles on different online platforms to one another. You can also use Orcid to tie all outputs of your digital identity together. And don’t forget to keep your very profile on the Commons up to date.

Make It Talk! Think of managing your digital academic identity as curatorial work. As you design your site and its content, think about the political and intellectual views you put forward via your digital identity, and what audience you are trying to appeal.

Compartmentalize. Separate the professional from the too personal. For example, you may not want to link your Twitter account to your academic profile (or keep a private profile in addition to your professional one) if you use it mainly to rant about your football team or to post funny cat memes.

Maintain. This is perhaps the most challenging aspect of the curatorial work. The way you design your landing page (e.g., whether you plan on it hosting a blog, or a podcast) should keep into account the amount of time you intend to spend on it. Good practice suggests setting at least some time aside at the end/beginning of each semester to update your information.

Now, what happened to that Lung Block project of mine, you might be wondering? Turns out that spending a few minutes updating my profile on Academia.edu did pay off. Two Bridges is no longer involved with the initiative, but through their encouragement, I began working with architecture historian Kerri Culhane and developed the project as part of my scholarship at The Graduate Center. We are going to be holding a satellite exhibition here and a larger one off-site at the Municipal Archives in the spring of 2019, while we are also negotiating the rights to create a permanent digital exhibition. But this is for another blog post.

One comment

Comments are closed.