Kelsey’s image: A photo of the GC anthropology program’s bookshelf in the lounge, while the books were still organized according not to author or topic but color. Impractical, yes, but more poetic.

Part 1: Taxonomies

I admittedly have hit my fifth year in the GC’s cultural anthropology PhD program and am nearing overdue on finishing my topic and area bibliographies for my second exam (date still TBD). These are bibliographies (hereafter referred to as “bibs”) meant to situate my proposed dissertation project that I must create, with guidance from my committee, and then defend to them during an oral exam. To create them, I have found myself at times desperately searching for scholarly publications that fit within certain topical, geographical, and disciplinary constraints. Working on these bibs has been my most direct experience so far in really thinking cognizantly about the practical uses of taxonomies for academic publications (something I have thought critically about on a theoretical level) to help in such searches. It has also been a particularly important instance where I need to meticulously track changes from draft to draft of a massive text file–but more on that a bit later in Part 2 of this post…

Most often I’m asking myself: Okay, where can I find an academic article or book by a PhD-bonafide anthropologist or at least a self-identifying ethnographer, that follows said ethnographic methods, and touches upon x, y, and z topics in a specific country or region? Or, in any country outside of the main region that my area bib already focuses on? And then of course there’s the work of tracking down a virtual or physical copy of the text and skimming it to see if it’s doing the kind of work I was looking for and if I agree with its approach and politics enough to cite it (not to say I don’t cite some things to critique them too)…

Ironically, by grouping citations together into subsections on my bibs in unique ways, I am attempting to counter some of the dominant categorizations that have defined such topical, geographical, and disciplinary areas of study; and to trace genealogies of how forms of power have shaped their construction and canonization. Yet, I can’t entirely escape the influence of these dominant categorizations, and find myself reproducing only revised versions of them through my groupings of citations. Additionally, I also find myself relying on these dominant categorizations, to a degree, in my library and academic database searches for citations.

As most librarians, archivists, and data information scientists, among others, have emphasized again and again: metadata is important. Metadata refers to a set of basic information that describes a particular dataset often within a larger dataset–for example, the basic information describing a book within a library, including what it’s about and what discipline(s) it falls into. Metadata is data about data. Hence “meta”. Yes, there great memes about this (e.g. sad metadata kitty).

But also, as again, many librarians, archivists, and data information scientists have emphasized: metadata is political. Metadata makes sources more or less findable in specific ways, and thus metadata–the included categories, and how those categories are constructed, interpreted, and applied–impacts the circulation of ideas included in those sources and the careers of scholars who published them. And the act of citation of course is political too. It’s a reproductive cycle: that which isn’t cited isn’t canonized and is more difficult to find; and that which is more difficult to find is less often cited when then stints authors’ careers and recognition. So, @CiteBlackWomen (among other people of color, non-binary folks, and women).

Meta-comment on metadata: I asked GC librarian Roxanne Shirazi for some recommended readings on the politics of metadata, and she suggested works by: Geoffrey Bowker and Susan Leigh Star (Sorting Things Out), Sanford Berman (Prejudices and antipathies: a tract on the LC subject heads concerning people), Amber Billey, Kimberly Christen, Emily Drabinski (“Queering the Catalog”), Hope Olson (The Power to Name), and Bess Sadler and Chris Bourg (“Feminism and the Future of Library Discovery”).

While there is still more groundwork to be made to critique and change the canon and the dominant classification systems used for organizing academic publications, as well as the methods of search engine algorithms (check out Safiya Umoja Noble’s Algorithms of Oppression and Meredith Broussard’s Artificial Unintelligence), current library and online search engine taxonomies have many helpful uses. They help researchers find things they are looking for! Or possible things that may fit into their current idea of what constitutes the thing that they think they are looking for… #phdstudentdilemma

But ultimately, still, library classification and search engine taxonomies help researchers find things. As Rafena Mustapha’s article in QC Voices emphasizes, “In today’s world of information overload, the swiftness with which we can find a particular piece of information depends on its position in the wider pool of data” (2018). As Rafena Mustapha reminds us, searching for a book in the library, where a multi-layered system for sorting is quite necessary, is much different than trying to find a book in your personal bookshelf where the books are not organized in any set order–unless your home books are beginning to amount to a small library.

This said, do scope out the library shelves, while you’re there to pick up a book! I’ve often found other books in the same section when I originally came to find just one, including books that ended up on my bibs. They were intentionally sorted together because of their common themes (with some limitations) after all.

Kelsey’s image: When you find that sweet spot in the library: HQ1236.5 (all on women’s movements) [a photo of two shelves of library books]

But, returning to the quest to find citations through online methods, I reached out to GC librarian Steve Zweibel for some advice. We tried doing a variation of searches on Academic Search Complete (a database available through the GC Library website here). In relation to a specific sub-topic of my topic bib, Steve recommended me to think about the perfect hypothetical paper that might exist and the hypothetical keywords that it would have to have. Then, we did searches using those hypothetical keywords utilizing best practices for all online searches, which included using: boolean terms (and, or, not), and quotations and parentheses (just like for algebra in math but for combining multiple search terms).

This ended up being a tricky way to find potential sources on a specific topic–emphasis on potential here (on the contrary, it’s a great way to find a specific source that you already know exists but e.g. can’t remember the full title). I think it is so tricky because most anthropologists–and many other social scientific, humanistic, and other scholars–pride ourselves on coming up with new concepts, or new ways of theorizing concepts, that we don’t often keep using the same words to describe such concepts. Different wordings of concepts are also often used to align with different bodies of theory, although they may be speaking to very similar topics. Search engines, like any computer function, do not understand concepts, but specific combinations of characters (such as words) that a person programs them to respond to in certain ways.

So Steve recommended another approach: to find an article that really speaks to the particular sub-topic of the bib that I’m searching for more sources on, scan the bibliography of that article for sources, and use the article’s keywords as search terms to find additional sources. Steve also recommended to click “Times Cited in this Database” to see publications where that article was cited, which often will point you to publications on similar topics. This is a method I’ve practiced before and found incredibly useful, although it can lead to many rabbit holes.

When meeting with Steve, we also discussed the AMAZING resource that is published bibliographies. I’d already come across Oxford Bibliographies (available here on the GC Library website), which is a database of discipline-specific annotated bibliographies by experts on those topics and regions. This is like the fairy godmother of resources to a student working on their bibliographies! I found it especially useful for identifying trends and shifts within the canon on that topic or region, and specific canonical citations. Steve pointed me to a GC Library lib guide on background and reference sources, which includes a subsection specifically on published bibliographies. I highly recommend checking out that lib guide!

Also, I strongly encourage folks to not be shy to talk through their bibliographies with fellow cohortians and other academic friends, generosity-permitting (in addition to your advisor and committee members, of course). This can be especially useful for those of us looking for recommended citations outside of the geographic area we are most familiar with. And sometimes old-fashioned person-to-person conversations draw us to sources we hadn’t yet encountered through library or online searches.

Lastly, in relation to the topic of taxonomies and search strategies, there is also some tech that can help with documenting citations when you find them. There are a variety of programs that will grab metadata from a web page about a source and save the metadata necessary to create a citation of that source for you, have an option for you to create groups and sub-groups to organize your citations, and allow you to export group(s) of those citations into a text file. Zotero is a great, free open-source option (and the GC Library hosts workshops on how to use it!). Zotero also provides options for collaborative group work and creating public citation lists, which may come in handy for other sorts of projects.

Part 2: Track changes

Another big learning experience for me with tech while working on these bibs has been about the uses of programs for tracking changes in text files. Specifically, I learned that there is a software that will track changes from draft to draft in a text file for you, taking a snapshot of a current draft when you tell it to!

I’ve been drafting these bibs for several months now (some months more than others :/). As I switch around my theorizing of the main topic and area for each bib, and the sub-topics within each bib, I move, add, and delete various citations, but I do this knowing that these changes are not permanent and may change the next time I meet with my advisor or when I meet with another committee member or I realize or rethink something. I may delete a group of citations I wanted to include, but couldn’t find a theorization to make them fit into, and later find the perfect place for them to be added back in!

Basically, tracking every insertion, deletion, and move of each citation in these bibs, and being able to easily identify and recover past deletions between specific drafts, has been really important for me in keeping my sanity as I develop and revise these bibs. And I managed to do so without the problem of having a folder of file titles like: bibs.draft1.doc bibs.draft2.doc bibs.draft3.doc bibs.final.doc bibs.finalFINAL.doc etc. AND without the problem of fretting over a Google doc freezing or crashing mid-edit, not to mention getting lost in an overwhelmingly long single stream of tracked changes to one file over the course of several months…

This is because, thanks to my training and duties as a GC Digital Fellow, I recently built up the practice and confidence to draft my bibs using a programming language called Markdown (and began drafting them in that language very early into my bib-writing process to avoid cross-platform havok) and a version control system called Git, which is both free and open-source. And I drafted the Markdown files–filename extension .md–using a plain-text editor (specifically, a free one called Sublime).

Now, Git, and its website kin GitHub–where you can share and view a repository made with Git, and is also free and open-source (although it was recently bought by Microsoft)–is great and has been a lifesaver for tracking changes on my bibs, but I wouldn’t recommend doing a major project using Git until you have had some practice and feel real comfortable using it. Git is pretty confusing at first, especially for folks not used to directly communicating with their computer through the command line. To learn more about what Git and GitHub are and how they work, especially for the less tech-literate, check out this awesome blog piece by Nico Castro of Red Badger on “Git and GitHub in Plain English”.

Another meta-comment: Thankfully, GC Digital Fellow Rafael Davis Portela is leading a workshop on Markdown on November 1st! Save the date: Thursday, November 1st, from 6:30-8:30 p.m. in GC room 9206–and find more information and register here. Also, the GC Digital Fellows teach Git and GitHub, as well as the command line and other useful programs, during our annual GC Digital Research Institute in January–keep an eye out for the call for applications this November! Also, our most recent curriculum on Git and GitHub is posted online, which one could try to follow along and teach themself.

So why is it worth the hassle to learn how to write in Markdown, install and figure out how to use Git, and set up a GitHub account linked to the computer where you installed Git? First, Markdown is a very simple programming language and isn’t hard to learn, and it allows for some other useful tricks too (such as quickly making a set of slides). Git and GitHub are a lot harder to learn. But, they allow you to do this:

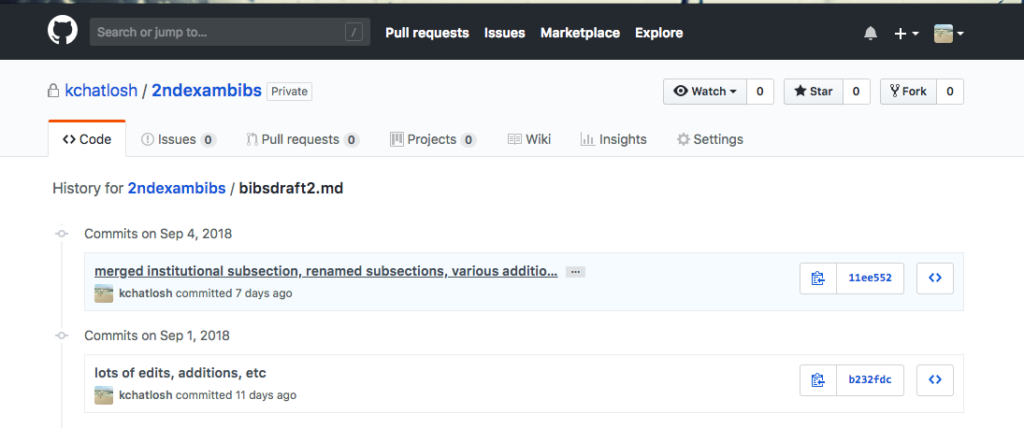

Kelsey’s image: A screenshot from the history of committed changes to the bibsdraft2.md file in my “2ndexambibs” repository on GitHub, with comments reminding me what changes I made (when you do the command: git commit -m “describe the changes here”)

![]()

Kelsey’s image: A screenshot from that same history of committed changes to my file on GitHub, after I clicked to view the specific changes (additions are in green, and deletions are in red) committed on September 4, 2018

And this is how I’ve kept my sanity. The more specific the descriptions I include when I commit changes (e.g. for the committed changes on September 4, 2018: “merged institutional subsection, renamed subsections, various additions”), the more sanity. This means I label when I take a snapshot of a draft, then find that specific draft, and dig into it and clearly see each and every inserted or deleted piece of text.

Yes, it took a lot of learning and practice with Git and GitHub, but in hindsight, the track changing capabilities has made that learning and practice very well worth it. And I’m pretty proud at my own advances at learning tech and putting it to work–indeed, as many in tech will tell you, using a digital tool for a specific project is the best way to really learn that tool. Honestly, I am generally not a very tech-savvy person. Just take a gander at the low-level tech I used when preparing for my first exam back after my first year of this PhD program:

Kelsey’s image: A photo of a door in my first NYC apartment covered in sticky notes with handwritten notes, organized by color, shape, and proximity.

Together, my growing skills in Markdown, Git, and GitHub; and what I have learned about library and search engine taxonomies and strategies for finding potential sources, have enormously helped me develop my second exam bibliographies. That said, no tech can help with the mental work of narrowing down and defining what works conceptually and politically for your own bibs in relation to your project (onwards to new PhD student dilemmas!) Nonetheless, hopefully, reading this post will help some others working on their bibliographies, or related work, too.